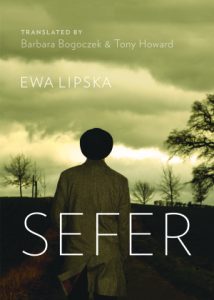

Ewa Lipska

Sefer

Journeys Through Memory – the Healing Image

Wednesday 7 May 2014, 6-8 pm.

Senior Common Room, 4th floor

UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies

16 Taviton Street, London WC1H 0BW

Registation

For further details please contact: u.chowaniec@ucl.ac.uk

“All of us, regardless of our historical situations, are hunting for our past….

We’ll always be talking it through with our psychotherapists, with historians

– today’s detectives.” Ewa Lipska

More about the author here

Programme:

- Introduction (Urszula Chowaniec)

- Reading: excerpts from Ewa Lipska’s novel Sefer (Ewa Lipska in Polish and Tony Howard in English)

- Discussion: Ewa Lipska, Francois Guesnet (UCL), Katarzyna Zechenter (UCL), Barbara Bogoczek , Tony Howard (Warwick University), Urszula Chowaniec (UCL/AFM KU)

- Q&A

- Reception and book signing

(with music based on motifs from Sefer)

Ewa Lipska, Sefer, English translation by Barbara Bogoczek and Tony Howard. Published in Canada by AU Press, Athabasca University Press, 2012

Free PDF available on the Publisher’s site here

Excerpts:

I had a remarkably original father. Father

owned the Sefer publishing house, which, although it

didn’t bring in any income, helped him cope with his

fear of depressive memories, and with claustrophobia.

Fortunately he also worked at an historical institute —

as a detective, because after all who but a detective can

write history. He left behind an unravellable will, with

which I’m still struggling today. I was an only child. In

my youth I dreamed of becoming a doctor, a solicitor,

a beggar, a musician, an actor, a demon, and a salesman.

But I went along with the wishes of my whole family,

read medicine, became a psychiatrist, and I practice

psychotherapy now. Thanks to which, I became linked

forever with the demons of our time.

***

The clerk stopped her work, looked at the postman and said:

“But that’s why my marriage collapsed. I predicted my

husband’s death.”

“What? Your husband’s alive, isn’t he?”

“Exactly. We were young, healthy, and in love, then one

night I dreamt I was in mourning. All that remained of

my husband in my dream was his absence. I woke up in fear

and trembling. He was still lying next to me. It seemed to

me he wasn’t breathing anymore. I tugged at his hand, and

I couldn’t believe it when he suddenly jumped up, asking

what had happened. Had something happened? Ludicrous

question, isn’t it? I began to cry a lot. I was weeping for

him. With every knock on the door, I expected a Notification

of Death. Meanwhile he kept on going out to work. And

coming back. I cooked him cranberry compote but behaved

like a widow. I started buying black dresses, blouses, jackets.

We began living a life after death. Something had to happen,

I knew. Because it was all predicted. One day my dead

husband, whom I so adored, applied for a divorce at the

district court . . . I don’t even know where he’s buried.”

She confirmed it by stamping another letter.

The postman asked, “Isn’t this work boring?”

“No. Why? There’s a different date stamp every day.”

***

On our way to the hotel Maria and I talked about

the double nature of language, which can suddenly flick

you from a smart sophisticate into a lout. Just a moment

ago language was entertaining us with the brilliance

of its wit and palette, only to announce suddenly in the

middle of the town square: “I’m kurwa trying to explain

it to him, and he just gobbles up his fucking sausages!”

Maria went back to rejoin her friends while I phoned

Doktor A. at the clinic. He read me part of a letter from

a patient whose history he’d tried to build into a case

study: “Dear Herr Doktor, why won’t I answer personal

questions? Because I never answer personal questions. Do

you remember what Goethe wrote about Werther? ‘Oh, how

often I’ve cursed those foolish pages that made my youthful

torments public property!’ We live in an age of collective

exhibitionism; we strip ourselves naked mercilessly, down

to the bare void. The void that traps us forever. And you,

Herr Doktor, think that I’ll tell you everything, undress down

to the last nerve. You all know too much about me anyway.

I bet when I’m wired up for my ECG, you’re recording the

love inside my heart. Nowadays everything belongs to

everybody and nobody.” Doktor A.: “So I arranged to

meet him outside the clinic. And in two hours he told

me much more than I would’ve got on the record.”

“And how’s your vegan blonde?” I asked. “Or is she

a kosher brunette now?” “Not yet, but you’d better

come back to Vienna soon. I don’t like diagnosing

over the phone.”

About the book:

Description

Lucy Popescu’s review

Justyna Sobolewska’s review

Also

Piotr Gwiazda’s review of Sefer in The Times Literary Supplement, Published: 22 February 2013;

Chris Miller’s review: The Warwick Review, Vol.VII NO.4 December 2013, p.14