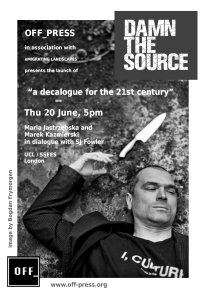

Migrants, Vagabonds and the Others: Damn the Source

Marek Kazmierski in conversation with Urszula Chowaniec and Wioletta Grzegorzewska

June 2013

This is your first full-length publication. Please tell us a bit about what your literary career has been until now and how this collection of short stories was put together?

It’s pointless to talk about “careers” when discussing writing. Maybe even harmful. I’ve wanted to be a writer, little else, since my university days. I then spent ten years working, travelling, doing all sorts of reckless research to have something to write about. It wasn’t until I finished a novel and tried to get an agent that I realised the world of publishing is far more complex and, in places, insidious than expected. I did what I was told to “become a writer” – penning columns in newspapers, attending and running creative writing workshops, getting short stories published here and there, teaching, lecturing, etc. Even though I was still working in refugee centres, prisons, bars and the like, just not to know I had not lost that sense of connection with life outside of literature. This collection came out of a desire to prove something else as well. To show I can write in different voices, from different perspectives, as opposed to what a lot of contemporary writers, especially men, do – writing from their own solitary and often ditchwater-dull perspective.

These stories are various tales on displacement, on migrants, nomads, people who are looking for their place, but not always finding it. To what extent is it your personal experiences of an emigrant, but also someone who lives in London, the European centre of migration on one hand and on the other to what extent is it the result of your observation of the social and political change in Europe of last 10 years?

All the stories in the book are true in the sense that they happened either to people I know or read about in the press. As true as literature can ever be. Ten years ago, I didn’t know a single Polish person on this island. Now, I know hundreds, and that is just those involved in cultural animation and social work. But the book is not about the here and now alone. I meant it to be universal – through experiences of a specific group of people in a specific time and place for it to say something about reality to anyone anywhere on the planet. Young, old. Free, oppressed. Simple, smart. I believe in literature as “essential entertainment” – layered so that anyone can get something out if in a myriad of ways. I would run a marathon if I had to face the prospect of having to read Joyce or Hughes or Milosz again. They wrote books for their high-brow pals, and that is death on the page for me.

Among the ten central characters those who stand out are outsiders, for whom the symbolic disconnection from a “source”, cutting off from their roots, has had a rather negative effect. Do you agree with this reading of the book?

I have to. In spite of how “dark” the book looks and reads, I am a blessed with a sunny disposition. Painful experiences wash off of me, and things other people find depressing I often find inspiring. But on a more macro level, I don’t expect art to cuddle. If the people we read about don’t hurt, and aren’t sometimes destroyed by their own folly, we will never take anything from art other than distraction, a betrayal of what the power of storytelling can and should do. Especially that now, after a few decades of consumerist comfort zone, the world is starting to spin in all sorts of worrying directions.

The title of your collection is intriguing and can be interpreted in many ways. Can you say something more about how you came to choose it?

Damn, I could, but I’d rather not. A great deal of thought went into it. I thought about selecting a title from one of the stories in the book, playing it a little towards convention, but then intuition whispered in my ear and the whisper was seductive enough. I think it sounds glorious, though the problem I am now faced with is trying to repeat it in Polish. It’s funny just how untranslatable certain words, phrases and concepts are. It is a trap I set for the reader. How they deal with it is their own story.

The subtitle of the collection is very intriguing: “a Decalogue for the 21st century”. The obvious – and also Polish – connotation is to Kieslowski series, but it is also a very strong moralistic standpoint: to propose a series of parables with strong moral lessons. Is this what you intended or perhaps it plays a sort of ironic subtext to the contemporary secular world, where clear religious commandments are constantly travestied?

Kieslowski was not a preacher. He often told ridiculously naïve parables, but when he hit his stride, he created incredible art. The best. And not without forethought. The way in which he created his Dekalog in the early ’80s, as a response to Communism and as a desire to get out of the ghetto his art was in at the time, this is something I can identify with. He put a lot of planning into that project, how he shot the films, and how two came to be cut as feature length movies. It made his name around the world, success I am trying to piggy back onto. I studied comparative religion, but I am not a spiritual person at all. A mystic, very much, but the idea of lecturing anybody about this or that, well, regardless of what ghosts or fairytales you believe in, is a recipe for awful art. I think we live in a very moral age, compared to the past, an age ruled by legislation and legal frameworks, but we are all too often too stupid to make the laws work for us. Hence blood has to flow.

There are a few themes which appear constantly throughout the book: the knife, the role of body as a way of communicating spiritual suffering or the clumsy linguistic communication between the newcomers and the native (the English as the language of the narrative or the inner teller of the book). How do you see the main role of these stories for English literature? What is the role of the Other in contemporary world? What do we learn from the foreigner?

The variety of knives which appear as a narrative device in all ten stories is a risky little McGuffin. Notice the cover of the book. The knife is held as a shield, not a weapon. I am hiding behind it, standing back. The one hovering in the corner is more a torch than a blade, hidden among all those leaves, and yet will people read it this way? Or will they just see darkness and obvious brutality? The body is absent from my writing, all too often, so including themes of sexual force, self-harm, family conflict, all that was necessary to overcome my weaknesses as a storyteller. But the knife also works in a number of other ways. As a gift. An artist’s tool. A catalyst for change. And setting all stories on one day, the day before Xmas Eve, was also a challenge. Stupid? Reckless? I guess Poles are seen and see themselves as such by our Others – Germans, Brits, Americans. I wanted to play on this stereotype, even refer to it in the first story, as something both real and unreal. The problem in the 21st century will be managing that duality – diversity and cohesion – hence the book sort of tries to liberate some of its characters, give them international perspective. They are off to the steppes of Russia, Sri Lanka, Chile, the States. And, of course, home, though not back to what it was before, as the characters themselves are no longer who they were when they left their “motherland”.

Which is your favourite story in the collection?

“Losing Light”. It broke my heart to live and broke my heart to write. Though now I would say the “light”, both subject and source, is very much found.

I have few favourite stories from the book, and one of them is “Elvis and the Third Sea”: what I like most is the effect of the foreign language. Zosia is telling her traumatic life story and revealing the most intimate experiences in imperfect foreign language, yet, it seems the perfect tool to do it: the trauma cannot be put in the correct grammar, it can only be told through drastic stammering, repetition, and half-broken sentences. You made the Ponglish a vehicle of expressing the suffering, while it usual the source of jokes and anecdotes. Tell us a bit about your choice of language for this story?

This one was difficult to write, both from the thematic point of view and the style I chose for the piece. Writing a monologue uttered by someone facing a foreign therapist, for the first time ever, trying to express something about self-harm, family history, a love which is both their liberation and damnation, was a tough call. Not sure one I answered fully. I worked very, very hard on getting the voice right. Reading it aloud over and over again, sending it to writer friends of mine, especially female friends. I wanted the character to be hobbled by her new tongue, but to have poetry too. She comes from a beautiful part of the world. And is in love. For the first time ever. That sort of grace must also come through in the language.

You have been translating Polish poetry for many years. Does the lyricism which demands you go deep into the mysteries of a language also affect your prose?

Not as much as it should. I want to write each line of my prose the way poets write verse, but I fear it is too intense. Readers will find it pretentious. Perhaps I am wrong. I need to get feedback, a great editor, a mentor. Writing is a solitary process in itself, but the business of creating stories to write about is so fundamentally collective. In this, translating hundreds and hundreds of amazing Polish poems in the past few years has been instrumental. Learning from the blades of masters.

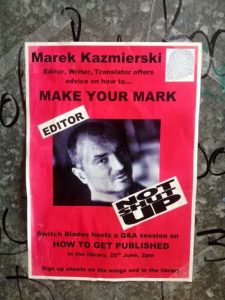

You have been working in and around prisons for many years and now you are the editor of Not Shut Up, the magazine that aims at presenting the creativity of people in jail and custody. How has this experience influenced your writing?

It has made me both more socially aware and more ruthless. The need to express ourselves through storytelling is in all of us, but it has been locked away in ivory towers of class and wealth. I want what I write and what I do till the day I die to be liberating, physically, emotionally, metaphorically, literally. Art, and the freedom it offers, comes with a very worrying price tag, but being deprived of access to it, and the permission to engage expressively, is far more costly to individuals and the communities they are part of.

The knife which appears in all ten stories can also be read in different ways, for example in Freudian psychoanalytics it symbolises “masculine rules” and the phallus. From previous interviews with you it seems your favourite writers are men: Stasiuk, Hemingway, Cormac McCarthy, Hunter S. Thompson, Graham Swift, Joseph Conrad, Bukowski. Do you consider literature to be gendered and if so is it in some ways shaped by this?

The knife is like truth – it can kill and it can save lives, depending on how it is applied. I read a lot when I was younger, mainly fiction, and stumbled upon a lot of male writers, who dominate all sorts of literary territories. In the past decade, however, I have read far more non-fiction. And spent far more time engaging with people rather than characters in books. Here, women win hands down. In poetry, for example, I find they often create much more satisfying work, less introverted, less pretentious. The novel I am working on now is written in the voice of a woman. It interests me more, always has done, though when I was younger perhaps I listened to men in trying to become one myself. Now, I am more focused on a universal, mystical brand of humanity. Gender is still very powerfully there, but it does not define the limits of what I am trying to say in writing any more.

In the closing, autobiographical piece, you state “I have a Polish heart and a English head, ad that is why I am happy”. Does such a dichotomy deliver happiness?

I wrote that piece to impress the Penguin judges. I guess it worked, as it ended up being one of the Decibel Prize winners, published in 2007. It is flawed (thankfully, I had the chance to edit it for this publication), but then again, yes, being wildly emotional and at the same time fiercely logical, I think, gives me improved chances of getting to where I am going. People who are a product of different cultures, as opposed to being “born and bred”, are made of alloy, a mix of compounds, lighter, way stronger than base metals, so here is another macho metaphor which fits.

At a certain point in your writing life, the work of the American playwright, screenwriter and actor Sam Shepard fascinated you. Do you think his style has in some way influenced your first book?

It was his prose and poetry which blew me away. Motel Chronicles and Hawk Moon, a book I have been going back to for 20 years and still find new things to discover. All great art transcends time, remains perennially fresh. Since he wrote it back in the ’70s, and then the script for Paris, Texas (also my favourite film), he has been rehashing the same old themes in more and more tired ways. A heartbreaking erosion of talent. But then again, Shepard, for all his cowboy mythologies, is one of the few writers I know willing to confront the idea of love head on. He did this better than any other writer I know. For that, he will always be my literary father figure.

According to your website, you are a kind of “renaissance man”. You paint, shoot documentary films, translate, publish books, travel, edit a literary magazine, take active part in London’s literary scene, organising events and festivals. How in amongst all that tumult do you find time to write?

I painted years ago. Have not shot a film in ages. Yes, it is possible to do a lot of things at once, but only up to a point. It took me a year of hard, hard work to ready this book for publication (some of the stories were started many years ago). People always give me earache for being involved in “too many” projects at once. They never ask for reasons behind what they see as madness. Technology means we can all now be jacks of many trades – web builders, film editors, recording artists, proficient photographers – but to become a master of anything, you need a lot of strands of light channelled into a lazer-like beam. Otherwise, you might as well be writing concrete prose on concrete themes for concrete trade publications.

What are your future literary ambitions?

These haven’t changed since I turned 20 – to write three ground-breaking novels and then retire to some far-off place to translate some of my favourite Polish authors. I have a novel and a half done, so half way there. After that, it will be time to do something else for literature. No writer should be allowed to produce any more than three novels in a row, without having to then translate three more from another language. Just to get away from themselves and back out into a world beyond their own mythologies. Think about all those names putting out books year after year, Polish, British, American. How tired and tiresome they have become. Some literary “coach” should call time-out and tell them to get over themselves. Sit out the next round. Watch and relearn. I am writing a play about just such a writer, but not sure what will happen to that project. Knowing how my “career” has gone so far, I may not see those woods for a while yet.

Recent Comments